Notes from Strong Product People

Page 28:

The method I use for doing a team assessment is called GWC, and it is described in Gino Wickman’s book, Traction. According to Wickman, GWC stands for get it, want it, and capacity to do it. These three parts of GWC can be turned into questions that you ask yourself as the manager/leader of PMs. Let’s consider each in turn:

- Does your PM understand (as they say, get) what their role is as a PM? And do they get what’s expected from them in this role in terms of outcome and output?

- If they get it, do they also want it? Is the work they do aligned with what they want to achieve in their career and personal life?

- And if they get what needs to be done, and they want to do it, do they have the capacity to do the job? Do they have what’s required mentally, physically, and emotionally to do their jobs? Do they also have sufficient time and knowledge and are they provided with enough resources?

Page 34:

So, then, what is a product?

A product is something created and made available to somebody that brings value to customers/users (the market).

When I describe what the one major responsibility of a product manager is in just a few sentences, I use Marty Cagan’s definition: It’s the product manager’s job to come up with a product solution that is valuable to the user, usable by the user, buildable by our engineering team, and still viable from a business perspective. It’s all about finding a balance between these four dimensions.

Page 47:

There are eight buckets in the PMwheel:

- Understand the problem. Are your PMs aware of the underlying problems the users are facing? Do they understand the motives, issues, and beliefs of the target audience? And have they thought about what the needs of the company/organization are?

- Find a solution. They found some good problems to solve? Great! Can they partner with the team and the stakeholders to come up with some possible solutions and an experiment for testing which of them is worth building?

- Do some planning. No matter if you are a fan of good old roadmaps, or you know the latest agile planning tricks, a PM must have a plan and a story to explain what’s next.

- Get it done! Every PM needs to know how to work with her product development team to get the product out to the customer.

- Listen & Learn. Once you’ve released something new, you will want to observe if and how people are using it and iterate on the learnings to improve the current status.

- Team. How good are the PMs when it comes to teamwork? What do they know about lateral leadership and motivation of teams?

- Grow! Are they investing some time in their personal growth as a product person?

- Agile. Are they just following what others exemplify as an agile way of working or do they fully understand Agile values, principles, and ways of working?

Page 51:

I have found that doing this in the most effective way possible requires five specific steps:

- Step 1: Get to know your PMs. Spend time with your product managers! Learn all about their strengths and areas for development, what they want to achieve in life, how they learn, and the extent of their PM know-how. You can also learn a lot about your PMs by talking with their peers.

- Step 2: Reflect on what you’ve learned and map it to your ideal. Take what you’ve learned and create your own PMWheel assessment of what you think your PM’s strengths are - and where is room to grow.

- Step 3: Ask your PM to assess themselves using the PMwheel or the framework you have decided to use. Compare this assessment with your own aessessment and discuss. What areas require further development?

- Step 4: Ask yourself: Can I help this PM get better in their development area? If not, who can you tap to help your PM improve? This step is an important one because few things are more frustrating for your PM than being told, “Your time management could improve,” without giving them some direction on where to start their journey.

- Step 5: Sit down with them and ask how they think they’re doing. This is perhaps the most important step of all. Explain to them the reflection you see (think of yourself as a mirror - reflect, don’t patronize). Talk about what they are doing well and together decide development areas for them to work on. Your PMs usually already know their areas for potential growth and what would be most helpful to them to improve - in their current role or toward the next, bigger challenge.

Page 56:

The results of a study of 300,000 leaders indicates that the top-five leadership skills most important for success are: inspires and motivates others, displays high integrity and honesty, solves problems and analyzes issues, drives for results, and communicates powerfully and prolifically.

Page 70:

If you have a long-term team member - a PM who has been with the organization for several years - and you think she is not a competent team PM, then it is your responsibility to address this situation as quickly as possible. Talk with the individual about your expectations for a competent team PM and offer your help to get them there in a reasonable time frame. It is not okay to ignore this any longer. As Steve Gruenert and Todd Whitaker say in their book, School Culture Rewired, “the culture of any organization is shaped by the worst behavior the leader is willing to tolerate.” Everyone is watching to see what the lowest level of PM performance is that you as HoP are willing to tolerate.

Page 100:

If I could recommend only one thing for you to do starting today, it would be to start creating a vision for every PM on your team and think about a good first step on this journey. Having this inner picture will immediately change the way you see and treat them.

Page 223:

The hypothesis-driven approach:

- Make observation

- Write down assumptions + quantify & prioritize them (optimize on max outcome)

- Write down proper hypothesis

- Evaluate with experiments

- Decide = accept or reject hypothesis

- Refine or take action on hypothesis (= new assumptions or start to build)

Page 272:

Your PMs will inevitable encounter difficulties with their teams. In his popular book, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, author Patrick Lencioni suggests that problems in teams can often be the result of these five dysfunctions:

- Absence of trust. An unwillingness to be vulnerable. Team members who are not genuinely open with one another about their mistakes and weaknesses make it impossible to build a foundation of trust.

- Fear of conflict. Teams that lack trust are incapable of engaging in unfiltered and passionate debate of ideas. They instead engage in veiled discussions and guarded comments.

- Lack of commitment. Without having their opinions aired in the course of passionate and open debate, team members rarely buy in and commit to decisions, though they feign agreement during meetings.

- Avoidance of accountability. Without committing to a clear plan of action, even the most focused and driven people often hesitate to call their peers on action and behaviors that seem counterproductive to the good of the team.

- Inattention to results. When team members put their individual needs (ego, career, recognition) or even the needs of their divisions above the collective goals of the team.

In my own experience, by turning each of these five team dysfunctions into a positive, you can see what kinds of behavior the members of truly cohesive teams engage in:

- They trust one another

- They engage in unfiltered conflict around ideas.

- They commit to decisions and plans of action.

- They hold one another accountable for delivering against those plans.

- They focus on the achievement of collective results.

Page 282:

Communication theorist Harold Lasswell developed a model of communication (commonly known as Lasswell’s communication model) that explains the communication process. I modified Lasswell’s model just a bit to make sure it still fits our 21st-century workplace. Here’s my take:

Who communications what via which channel to whom with what reason and effect?

… In a business context, we communicate to …

- Form and maintain relationships;

- Give, receive, and exchange information;

- Persuade and influence;

- Alleviate anxiety and distress;

- Regulate power;

- Provide intellectual and emotional stimulation;

- Express emotions and explain our thoughts and opinions;

- Brainstorm and problem solve; and

- Seek alignment on a certain topic or to agree on a shared goal.

Most of these nine reasons why we communicate all boil down to one thing (and this is the +1): expressing wants and needs.

Page 303:

If the answers to all those questions are promising, I call it an opportunity and I’m happy to add it to the discovery backlogs. If it’s hard to answer these questions, you know it’s not the right time to prioritize this idea.

- What are the underlying assumptions of this idea and have we understood the underlying customer problem?

- Are you currently in the right position to validate these assumptions and what would it roughly take to validate them? (Massive experimentation or just a little bit more desk research?)

- How dangerous are the underlying assumptions? (Would it be devastating if we think we are right, then we build the thing and learn we were not right?)

- Is there any business potential and how big might it be? (If not, this diea should be killed now!)

Page 322:

When your PMs create the compelling stories they will use to inspire their teams, stakeholders, and others, they should be sure to hit the following points:

- Paint a desirable future/big dream.

- Explain why someone should be a part of the story.

- It’s good for you

- It’s good for us

- It’s good for all

- Assess the anticipated difficulties and why it’s worth the effort.

- See their world

- Appreciate them as human beings

- Communicate understanding

- Present the shared goal. Create a sense of urgency and present information that enables action.

To overcome the paralyzing fear of the blank page, I like to start PMs with the following short task (which, in time, can become a complete story). PMs simply will in the blanks with their own situation, providing them with the basic elements they need to create a compelling story:

- We want to __

- In order to __

- Because if we don’t, __

Page 332:

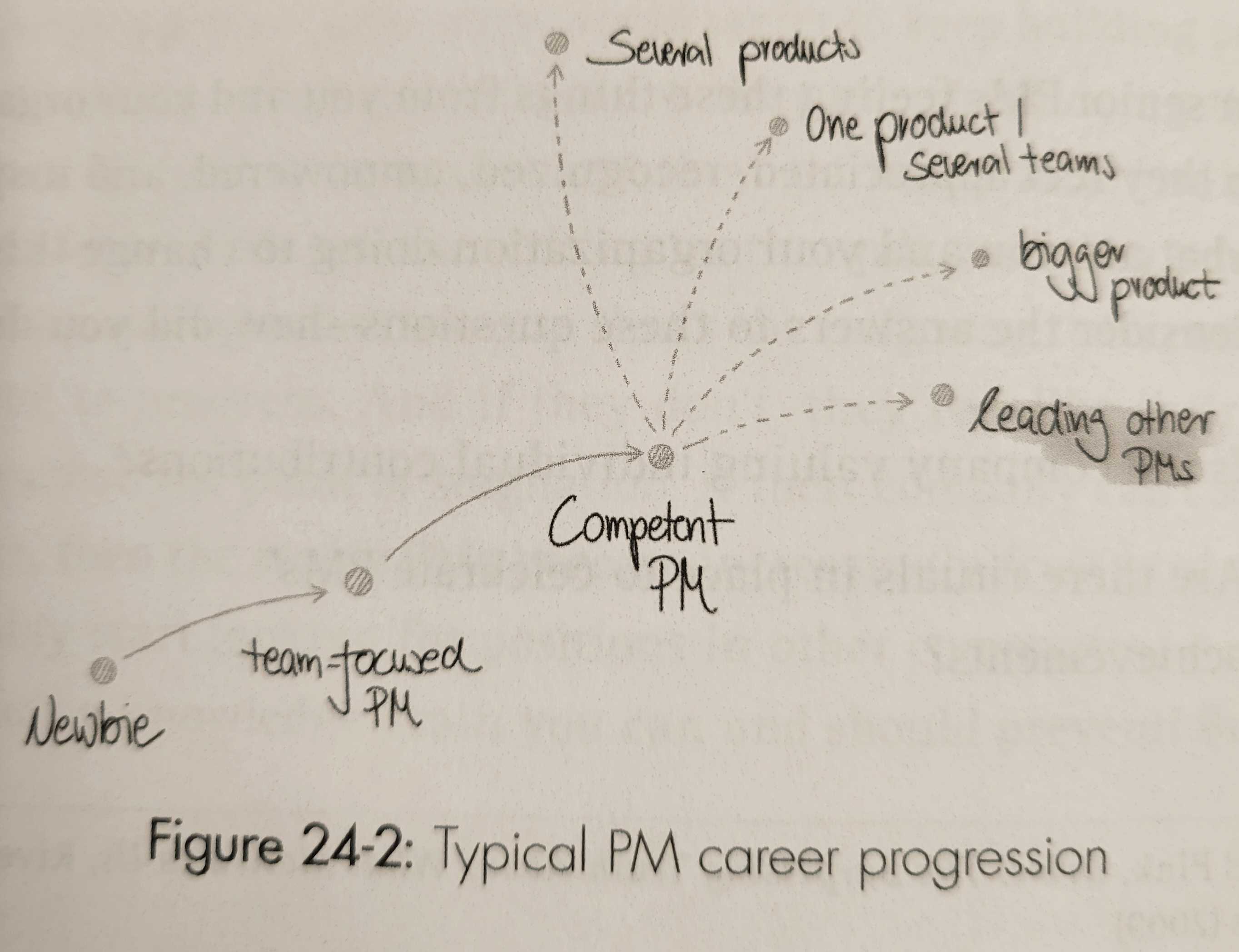

When senior PMs reach full competence - where they have the skills needed to get the job done - the need to decide in what direction to take their careers. There are four ways for PMs to continue their personal growth and grow their careers:

- They can start to manage a bigger, more important/successful product.

- They can start to manage several products.

- They can manage a product that is too big to be handled by one team.

- They can manage other PMs.

While the third item this list can be partially a management role, the last on is clearler on the people-management path, and therefore, not for everyone.

Page 351:

When I think about how we can foster bottom-up change in our organizations, I am reminded of the words of Götz Werner, founder of dm-drogerie markt, Germany’s largest retailer in terms of revenues (more than $12 billion). He once said, in German, “Führen heißt nicht, Druck aufbauen, sondern einen Sog erzeugen.” In English, this translates roughly to: “Leading does not mean building pressure, but creating a pull.” In other words, the best leaders don’t push their people to do things - they provide the conditions that draw employees into the work they are responsible for of their own accord, fully engaged and inspired to give the very best of themselves every day.

Page 364:

However, some organizations and the people in them are well-suited to dealing with conflict - it’s not a big deal for them. I have found that, when this is the case, there are usually several things these organizations all share in common:

- Their employees are empowered and encouraged to resolve conflicts that arise in their direct environment on their own. At the same time, they are encouraged to escalate as early as possible if they can’t figure things out on their own.

- Their employees know how to personally deal with their first reaction/emotions when they find themselves is a confrontational situation. And they know how to overcome this first rush of hormones to figure out what the real problem is.

- Everyone makes sure that, not only does the current conflict get resolved, the system gets an update so that this ideally never happens again. (Example: HoPs can make sure to talk with other department heads to resolve conflicting goals of two teams, fighting for resources, and so on)